*Abhishek Sharma,

* Senior Resident, Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi

Introduction

Uric acid is an end-product of purine metabolism (1). Hyperuricemia is primarily caused by increased uric acid synthesis and decreased renal excretion (HUA). (1). Notably, HUA has been reported to be the second most common metabolic disorder worldwide, after diabetes. (2). A nationwide survey conducted in the United States found that a significant percentage of people (20.0% of women and 20.2% of men) have HUA. (3). According to a recent Chinese study, the prevalence rate of HUA rose gradually between 2000 and 2017, rising from 8.5 to 18.4%. (4)

Based on the most recent estimates from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD), 41 million people globally suffer from gout, which is the most frequent cause of inflammatory arthritis. (5). According to the 2015–2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) survey out of 9.2 million of US population, 3.9% of adults have gout. (3). Unfortunately, despite advances in our understanding of the disease’s pathophysiology and available treatments the burden of gout remains high and management of gout remains suboptimal.(6). The additional burden of comorbidities, which are common in gout patients and are linked to increased morbidity and mortality risk, such as hypertension (75%), obesity (53%), chronic kidney disease (CKD) (70%), and cardiovascular disease (CVD) (10% to 14%), augments the burden of gout. (7). Patients with gout also have a higher incidence of metabolic syndrome (8), and asymptomatic hyperuricemia is more prevalent in individuals with metabolic syndrome (9,10). Several chronic illnesses that are common in gout are significantly influenced by food, and it is also hypothesized that diet contributes to hyperuricemia and gout by increasing the formation of urate owing to dietary purines. The potential implications of dietary approaches in gout care have drawn a lot of interest, given the importance that diet and metabolic factors play in many common comorbidities in gout patients as well as the knowledge that certain foods contribute to serum urate.

In this review, we emphasize on dietary strategies and specific aspects of diet that have been studied for their effects on gout and hyperuricemia.

Production and Excretion of Urate:

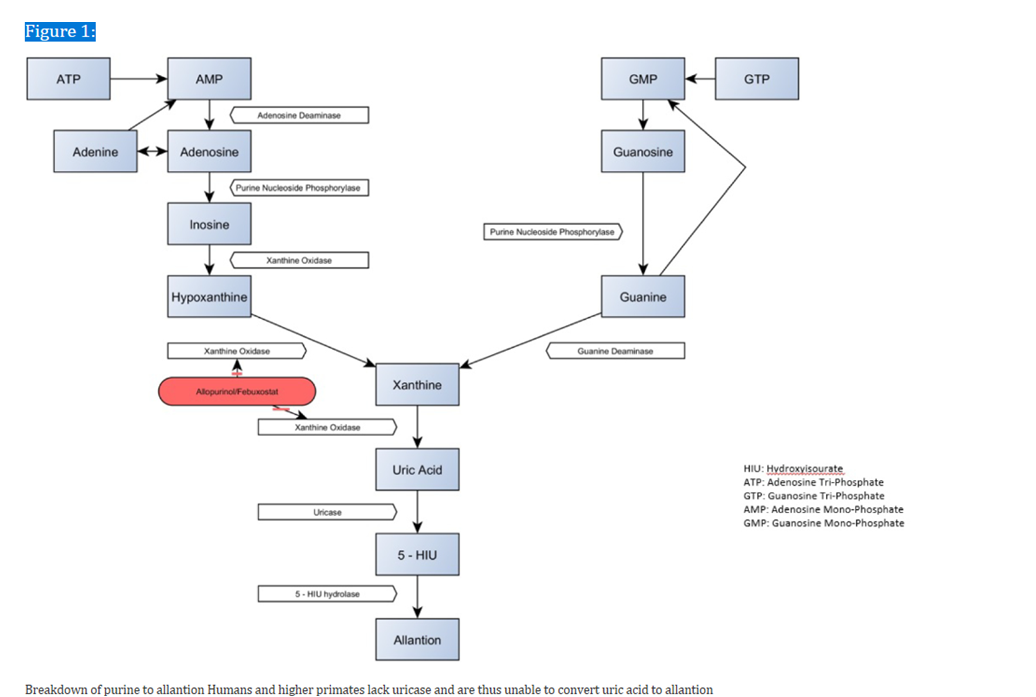

Purine nucleotide bases adenine and guanine are essential for the synthesis of DNA and RNA as nucleosides (adenosine, guanosine). They facilitate the transport and use of cellular energy as triphosphates , such as ATP. They are important for neurotransmission and are also parts of co-enzymes. (11). Purines are therefore essential for healthy human physiologic function. Purine metabolism produces urate, which is why purines are linked to gout, even though most people do not have hyperuricemia as a result of this process. The conversion of purines into uric acid is the result of many enzyme processes. (Figure 1).

Nucleotidases convert the monophosphates adenosine monophosphate (AMP) and guanosine monophosphate (GMP) into adenosine and guanosine, respectively. Adenosine deaminase converts adenosine to inosine, which is further metabolized into hypoxanthine by purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP), which is metabolized into xanthine by xanthine oxidase, and ultimately into urate. In a similar manner, PNP metabolizes guanosine into guanine, which is further metabolized into xanthine by guanine deaminase, which further metabolizes it into urate. These steps in purine metabolism are illustrated in Figure 1.

In several organisms, the enzyme uricase breaks down urate to 5-hydroxyisourate as a last step before excretion. Allantoin, which is highly water soluble, is then eliminated by the kidney. However, Uricase is absent among humans and higher primates like chimpanzees and gorillas. The final result is therefore urate, which needs to be actively excreted because it is not water soluble. As a result, these organisms have higher urate levels in their blood. (12). When urate levels exceed 6.8 mg/dL, crystallization can occur, which then ultimately leads to clinical manifestations of gout.

Either urate overproduction, renal and/or gastrointestinal underexcretion, or both, can lead to hyperuricemia. (13), though underexcretion is the predominant cause of hyperuricemia in people with gout (14) (15). The diet contributes about one-third of the body’s urate pool, while endogenous production accounts for about two thirds. (16). Urate underexcretion is the main problem associated with gout. The kidneys eliminate around two thirds of the urate, with the gastrointestinal system eliminating the remaining portion.

Dietary factors, hyperuricemia and gout:

It remains controversial to determine whether dietary management can be used in addition to medicine to improve gout management and/or as a treatment option for patients who do not yet meet the criteria for urate-lowering therapy. There is ongoing debate regarding how much food affects gout management. Hyperuricemia in gout is largely caused by underexcretion of urate, and endogenous purine metabolism rather than exogenous food sources accounts for most urate synthesis. (16). Nevertheless, using xanthine oxidase inhibitors to reduce urate synthesis has been the most widely used pharmacological strategy for managing gout. Urate production would also be significantly influenced by dietary factors, albeit some may also have an impact on urate excretion.

Here, we discuss weight loss strategies, diets like the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH), Mediterranean, and low-purine diets, as well as certain foods including dairy, alcohol, caffeine, and high-fructose corn syrup.

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Diet:

Initially, the DASH diet was created for managing hypertension. The diet is centered around plants and includes plenty of fruits, vegetables, nuts, low-fat and non-fat dairy products, lean meats, fish, and chicken along with whole grains and “heart healthy” fats. It suggests consuming red meats, sweets, sugar-filled drinks, saturated fat, total fat, and cholesterol in limited quantity.

A number of studies have given insight on how the DASH diet effects serum urate levels in samples of non-gout. A secondary analysis of the initial DASH RCT showed that the DASH diet reduced blood urate by 0.22 mg/dL in people with hypertension but without gout, while the usual American diet reduced serum urate by 0.03 mg/dL. Despite the little drop in mean serum urate, there was a statistically significant difference between the two groups (18). A diet high in fruits and vegetables was given to the third group, and this was linked to a 0.17 mg/dL decrease. There was no discernible difference between the fruit and vegetable diet and the DASH diet.

An analysis of a participants of the DASH-Sodium trial participants who did not had gout demonstrated that those following the DASH diet group (mean baseline urate 6.6 mg/dL) reduced their urate levels by 1 mg/dL by day 90, while the control group, following a diet isocaloric to the DASH diet and comparable to the American Diet (baseline urate 6.7 mg/dL), noticed a reduction of 0.1 mg/dL (19)..

A protein-rich DASH diet had little effect on serum urate, with a 0.16 mg/dL reduction, according to a secondary analysis of the Optimal Macronutrient Intake Trial to Prevent Heart Disease feeding trial (OmniHeart), which was done among individuals with prehypertension or hypertension (20).. Notably, people without gout were included in these studies regardless of their serum urate levels determining their enrollment (i.e., hyperuricemia was not a exclusion criteria).

One study sheds light on how the DASH diet impacts urate levels in gout patients. 43 individuals with gout were randomized in this pilot crossover RCT to receive self-directed groceries (SDG) or dietician-directed groceries (DDG) based on the DASH diet in the first block and switched over without a washout. The DDG group showed a 0.55 mg/dL drop in serum urate, while the SDG group showed no change in this parameter. There were no general changes between the two periods, but in the second half of the study, the results were opposite, with the SDG group’s serum urate decreasing by 0.48 mg/dL and the DDG group’s by 0.05 mg/dL (21).

Regarding the impact of the DASH diet on the likelihood of acquiring gout, a cohort study carried out as part of the Health Professional Follow-up Study revealed that decreased risk of gout development was linked to higher DASH diet scores (22). 44,444 males without a history of gout were followed-up for 26 years as part of this study. Throughout the course of the follow-up period, 1731 incidences of gout were recorded. Gout risk was 32% lower in men in the highest percentile of the DASH dietary pattern score than in those in the lowest quintile. On the contrary, among men in the highest quintile of the Western dietary pattern score compared to the lowest, the relative risk of having gout was 1.42.

Given the modest decrease in serum urate with the DASH diet among people without gout, and minimal data to date in people with gout, it is unclear that a meaningful impact on clinically relevant outcomes in gout would be realized with the DASH diet alone.

Because there is generally low quality evidence among gout patients, the 2020 ACR guideline for the management of gout does not contain specific recommendations about the DASH diet. (23)

The Mediterranean Diet:

The Mediterranean diet places a strong emphasis on consuming whole grains, fish, plant proteins, and monounsaturated fats like olive oil. It also calls for consuming wine in moderation and consuming less red meat and processed carbohydrates. (24). The Mediterranean diet has been linked to a decreased risk of coronary artery disease and an increase in longevity, particularly when extra virgin olive oil or nuts are added. (25), (26).

A subsequent analysis of the PREvención with DIeta MEDiterránea trial, which included 4,449 older adults at high cardiovascular risk but who were not selected with regards to gout, revealed a negative correlation between the incidence of hyperuricemia and higher Mediterranean diet scores. (27). However, in a secondary analysis of the 235 obese participants in the Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial (DIRECT), there was no difference in the reduction of serum urate between patients assigned to low-carb, non-restricted calories, low-fat, or Mediterranean diets over a two-year period, including those with baseline hyperuricemia. (28). Overall, the serum urate level dropped by nearly 0.4 mg/dL, 0.2 mg/dL, and 0.3 mg/dL, respectively in the 3 groups. This suggests that, in comparison to other diets, the Mediterranean diet does not significantly lower urate levels. Unadjusted for a genetic risk score in the meta-analysis by Major et al., the DASH diet explained 0.28% variance in blood urate , compared to 0.06% for the Mediterranean diet. (17). The Mediterranean diet was found to be less effective than the DASH diet in lowering blood urate levels, despite the fact that the effects of both diets on urate levels were negligible. The effects of the Mediterranean diet on flare-ups and tophi are unknown because studies involving gout patients have not yet been done.

Like the DASH diet, the 2020 ACR guideline for the management of gout does not specifically recommends the Mediterranean diet because there is insufficient data from gout patients and an overall low quality of evidence.(23)

Low Purine Diet:

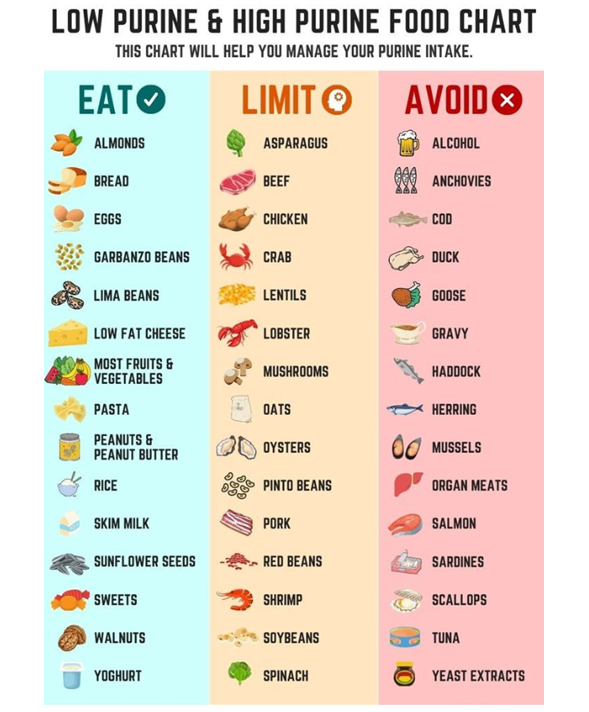

By avoiding foods high in purines, one can theoretically reduce urate, the byproduct of purine metabolism in humans, by following a low purine diet. Foods high in purines, such as shellfish, organ meats, alcohol, and canned fish like sardines, should be avoided based on this diet. Low-purine diets have been suggested as a gout management strategy, but there is a lack of data on how well these diets work in terms of gout outcomes. Furthermore, purine reduction or elimination results in the substitution of other dietary components; in Western diets, this may often mean a higher consumption of carbs and fats as a means of compensating for the unappealing and difficult to maintain low purine diets. Furthermore, a low purine diet is thought to reduce mean serum urate by approximately 1 mg/dL; hence, urate lowering therapy is still required to achieve goal uric acid levels regardless of a strict diet. Consuming foods high in purines has been linked to an increase in serum urate and an increased risk of incident gout in individuals without gout. (30, 31). For instance, the males in the highest quartile of meat consumption compared to those in the lowest quintile had a 1.41 times higher chance of developing gout, according to the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study.

Regarding the effect of reducing purine intake on serum urate in gout patients, a small retrospective study including 40 obese patients with gout found that patients who had a low-purine diet followed by sleeve gastrectomy for a year experienced a significantly higher reduction in serum urate, a lower frequency of gout flare-ups, and a lower need for allopurinol than patients who followed a normal purine diet. (32).

The 2020 ACR guideline for managing gout conditionally recommends limiting purine intake regardless of disease activity (23).

Role of Weight Loss:

Obesity is highly prevalent worldwide, with 1.9 billion adult population reported to be overweight or obese.(33) Greater BMI is associated with an increased risk of hyperuricemia and gout in a variety of studies . Increasing weight was linked to a rise in serum urate over time in the Normative Aging Study, although individuals without weight gain also experienced a general increase in serum urate over time. Nevertheless, weight gain was the most significant factor associated with a rise in serum urate above the baseline level. (34). Observations on the risk of incident for gout in both men and women have been added to these concerning serum urate. For instance, the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study revealed that amongst men the incidence for gout was associated with increased weight and obesity. (35).

The impact of weight loss on the risk of gout has been the subject of relatively few studies. Over the course of a 12-year follow-up period in the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study, weight loss was linked to a decreased incidence of gout. (35). IOver a median of 19 years of follow-up, 1982 people who underwent bariatric surgery had a reduced incidence of gout than those 1999 people who were obese but did not undergo the procedure. This illustrates the impact of greater degrees of weight loss. (36).A meta-analysis conducted in 2019 included 20 studies involving more than 5000 individuals to assess the impact of bariatric surgery on serum urate and gout. The majority of the included studies featured a minimum 12-month post-treatment duration. In all these studies, the mean serum urate dropped by 0.73 mg/dL in the third post-operative month and continued to drop by 1.91 mg/dL at the three-year mark (the pre-operative mean serum urate level was 6.5 mg/dL). (37).

A 2017 systematic review that examined the impact of ten longitudinal studies on the influence of weight loss in overweight and obese patients with gout provided an overview of the data about this topic. (38). Two studies established a dosage response association between weight reduction and both serum urate and gout flares, whereas six studies demonstrated the beneficial effects of weight loss on gout flares. A retrospective analysis of 147 obese individuals who underwent bariatric surgery revealed that 67 of the patients who had neither hyperuricemia nor gout, and had a baseline urate was 5.41 mg/dl. After an entire year, this group’s mean serum urate decreased by 0.46 mg/dl. After a 12-month study period, the mean serum urate of a subgroup of 55 hyperuricemia patients (mean baseline serum urate of 8.01 mg/dl) decreased by 1.68 mg/dl, while the mean serum urate of the 25 gout participants (mean baseline serum urate of 9.15 mg/dl) decreased by 2.75 mg/dl. (39)

Gout flare-ups and blood urate levels decreased in another small retrospective study of patients with gout undergoing bariatric surgery (40). 56 gout patients who did not undergo surgery were compared to 99 gout patients who had bariatric surgery in this study. Gout flares were more common in the first post-operative month among patients who underwent bariatric surgery (17.5% of the surgery group vs 1.8% in the control group). However, over the next 12 months, gout flares significantly decreased in the bariatric surgery group compared to the controls (18.2% to 11.1% in controls and 23.8% pre-operatively to 8% post-operatively). Serum urate levels were also found to be significantly lower in the group that underwent bariatric surgery (mean ± SD 9.1 ± 2.0 mg/dL at baseline vs. 5.6 ± 2.5 mg/dL, 13 months after bariatric surgery), while the control group showed no discernible change (7.7 ± 2.0 mg/dL at baseline in the control group vs. 7.0 ± 1.6 mg/dL 13 months later).

Regardless of disease activity, the 2020 ACR gout treatment guideline conditionally supports utilizing a weight loss program (no specific program supported) for individuals with gout who are obese or are overweight. (23).

Role of Individual Foods:

Many foods have been studied over the past few decades mainly for their effects on hyperuricemia; very few research have looked at their impacts on gout outcomes. here, we cover high-fructose corn syrup, dairy, omega-3 fatty acids, alcohol, caffeine, cherries, and vitamin C.

Alcohol

Although there is conflicting information about the effects of different forms of alcohol, alcohol has long been anecdotally linked to hyperuricemia and gout. Serum urate increased considerably with increasing beer or liquor intake but not with increasing wine intake, according to the third NHANES study, which included 14,809 participants (41). In addition, the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study, which included 47,150 male participants free of gout, found a significant association between alcohol consumption and an elevated risk of gout, with beer carrying a higher risk than spirits. They did not, however, find that moderate wine intake increased risk of gout. (42).

A few studies examined at how alcohol affects gout sufferers. The results of a small study of gout patients showed that patients who limited or abstained from alcohol had a lower serum urate (1.6 mg/dL) than those who did not, and that patients with heavy alcohol consumption (multiple gout flares) responded poorly to allopurinol. The study included 21 heavy drinkers (30 units or more per week), 8 moderate drinkers (less than 20 units per week), and 9 patients who rarely or never drank alcohol. The scientists came to the conclusion that the hyperuricemic effects of alcohol with combination of poor allopurinol adherence were probably the causes of these outcomes. (43)

The 2020 ACR guideline for the management of gout conditionally recommends restricting alcohol intake in gout patients, irrespective of disease activity, in light of the evidence from these observational studies. (23).

Caffeine, Coffee, Tea:

Data from the third NHANES survey (1988–1994) were also looked at to study the correlation of caffeine, tea, and coffee on serum urate (44). Individuals who consumes four to five cups of coffee or more had serum urates that were 0.26 mg/dL and 0.43 mg/dL lower, respectively, than those who did not drink any coffee (the baseline mean serum urate was 5.32 mg/dL). Additionally, there was a noteworthy inverse relationship between serum urate and decaffeinated coffee. But there was no correlation found between serum urate and tea or total caffeine intake (i.e., accounting for caffeine from all sources, including coffee, tea, and cola). Additionally, a study conducted on Japanese volunteers showed no correlation with tea consumption and serum urate levels, but an inverse relationship with coffee consumption. (45). A validated food frequency questionnaire was used in the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study to evaluate 45,869 men without gout for their use of coffee, decaffeinated coffee, tea, and total caffeine (46). 757 new cases of gout were documented during the study’s 12-year follow-up period. The risk of developing gout was strongly inversely related with increasing coffee use. Similar to the results for serum urate, decaffeinated coffee was also significantly inversely linked with risk of gout, although tea and total caffeine intake were not associated. Another study used a validated questionnaire to investigate the relationship between total caffeine intake, coffee, and tea with the risk of gout in the Nurse’s Health Study (47). 89,433 female participants had a 26-year follow-up period during which 896 cases of gout were confirmed. Compared to people who did not drink coffee, the risk of developing gout was 22% lower for those who consumed 1-3 cups daily and 57% lower for those who consumed more than 4 cups. The incidence of gout was likewise inversely related with more than one cup of decaffeinated coffee per day. Tea again did not showed association with gout. However, the processes underlying these relationships remains unclear.Of note, caffeine has a chemical structure similar to allopurinol, and thus merits further evaluation in patients with gout.

The 2020 ACR guideline for the management of gout does not make any recommendations regarding coffee, tea or caffeine intake.

Dairy:

Higher dairy product consumption has been associated with a decreased risk for gout and a lower serum urate in population-based studies including people without a diagnosis of gout (31,48). This was explained by the possibility that dairy products had a hypouricemic effect. Dairy components including GMP and G600 milk fat extract have been shown in an in vitro investigation to decrease Interleukin 1β. This suggests that they may help prevent gout by reducing the inflammatory response to monosodium urate (MSU) crystals (49). A randomized controlled crossover trial was then carried out to study these findings in a clinical setting. Eighty grams of protein from a soy control, early and late season skim milk (late season skim milk is rich in orotic acid, which is a uricosuric agent), and ultra-filtered milk protein isolate-85 (MPI-85) were given to sixteen male participants in the study who had no prior history of gout (50). Over the course of three hours, serum urate dropped by 10% in each of the milk groups; this drop is believed to be attributable to increased urate excretion. In contrast, the soy group experienced a 10% increase in urate. After that study, an RCT was conducted on 120 gout patients who experienced recurring flare-ups. The subjects were randomized to receive lactose powder control, skim milk powder (SMP), or SMP supplemented with glycomacropeptide (GMP) and G600 (51). All three groups experienced a reduction in the frequency of gout flares, with the SMP/GMP/G600 group experiencing a much lower frequency of gout flares than the other two groups. The 2020 ACR treatment guideline refrained to recommend an amount of dairy protein intake due to the lack of data addressing typical dairy products in individuals with gout (23).

High Fructose Corn Syrup:

The acute effects of fructose were revealed in a small metabolic study involving 17 participants (6 adults without gout, 6 patients with gout, and 5 children of patients with gout). Within 2 hours of ingesting 1 g fructose per kg body weight, the average blood urate rose by 1-2 mg/dL (52). There have also been observed long-term effects on serum urate. Higher blood urate levels were associated with the use of sugar-sweetened beverages in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988–1994) (53). High-fructose corn syrup has also been associated with increased risk of incident of gout in the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study. (54,55) .

The 2020 ACR guideline for the management of gout conditionally recommended limiting high fructose corn syrup intake regardless of disease activity (23).

Conclusion:

The available evidence regarding impact of diet on hyperuricemia and gout is largely limited to studies among people without gout. A small amount of serum urate may be affected by different dietary approaches, but for the majority of gout patients, these effects will not be sufficient for adequate gout management. As a result, these dietary approaches should only be considered adjunctive measures, with pharmacologic therapy serving as the mainstay of management in order to achieve the degree of urate-lowering required to control gout disease activity. Because diet has a minimal effect on serum urate and urate underexcretion plays a significant role in the pathophysiology of gout, healthcare professionals should be careful not to engage in dialogue that places the patient at fault. Instead, they should encourage medication adherence counseling and frame diet-related discussions as adjunctive.

Studies, and preferably trials, on gout patients are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of various diets on outcomes that are clinically relevant to gout, like flare-ups and tophi. Supporting observational studies suggest that alcohol and purines, especially those derived from animals, may have an effect on flare-ups. Avoiding or reducing high fructose corn syrup may also have other positive health impacts. Losing weight has many other positive health effects in addition to perhaps helping gout sufferers experience fewer flare-ups. Therefore, dietary modifications may be beneficial in some patients where excessive variables (such as weight) may be at play; however, the available findings continue to emphasize the importance of pharmacologic management of gout as the cornerstone for effective disease control.

References-

- Richette, P, and Bardin, T. Gout. Lancet. (2010) 375:318–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60883-7

- Chinese multidisciplinary expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of hyperuricemia and related diseases. Chin Med J. (2017) 130:2473–88. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.216416

- Chen-Xu, M, Yokose, C, Rai, SK, Pillinger, MH, and Choi, HK. Contemporary prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the United States and decadal trends: the National Health and nutrition examination survey, 2007-2016. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2019) 71:991–9. doi: 10.1002/art.40807

- Li, Y, Shen, Z, Zhu, B, Zhang, H, Zhang, X, and Ding, X. Demographic, regional and temporal trends of hyperuricemia epidemics in mainland China from 2000 to 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Health Action. (2021) 14:1874652. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2021.1874652

- DALYs GBD, Collaborators H. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1859–922.

- Li Q, Li X, Wang J, Liu H, Kwong JS, Chen H, et al. Diagnosis and treatment for hyperuricemia and gout: a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e026677.

- Singh JA, Gaffo A. Gout epidemiology and comorbidities. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50(3S):S11–S6.

- Choi HK, Ford ES, Li C, Curhan G. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with gout: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(1):109–15.

- Liu CW, Chang WC, Lee CC, Chen KH, Wu YW, Hwang JJ. Hyperuricemia Is Associated With a Higher Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in Military Individuals. Mil Med. 2018;183(11–12):e391–e5.

- Choi HK, Ford ES. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in individuals with hyperuricemia. Am J Med. 2007;120(5):442–7.

- Maiuolo J, Oppedisano F, Gratteri S, Muscoli C, Mollace V. Regulation of uric acid metabolism and excretion. Int J Cardiol. 2016;213:8–14.

- Álvarez-Lario B, Macarrón-Vicente J. Uric acid and evolution. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49(11):2010–5.

- Ichida K, Matsuo H, Takada T, Nakayama A, Murakami K, Shimizu T, et al. Decreased extra-renal urate excretion is a common cause of hyperuricemia. Nat Commun. 2012;3:764.

- Perez-Ruiz F, Calabozo M, Erauskin GG, Ruibal A, Herrero-Beites AM. Renal underexcretion of uric acid is present in patients with apparent high urinary uric acid output. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47(6):610–3.

- Choi HK, Mount DB, Reginato AM. Pathogenesis of gout. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(7):499–516.

- Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M. The changing epidemiology of gout. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3(8):443–9.

- Major TJ, Topless RK, Dalbeth N, Merriman TR. Evaluation of the diet wide contribution to serum urate levels: meta-analysis of population based cohorts. BMJ. 2018;363:k3951.

- Juraschek SP, Yokose C, McCormick N, Miller ER 3rd, Appel LJ, Choi HK. Effects of Dietary Patterns on Serum Urate: Results From a Randomized Trial of the Effects of Diet on Hypertension. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(6):1014–20.

- Tang O, Miller ER 3rd, Gelber AC, Choi HK, Appel LJ, Juraschek SP. DASH diet and change in serum uric acid over time. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36(6):1413–7.

- Belanger MJ, Wee CC, Mukamal KJ, Miller ER, Sacks FM, Appel LJ, et al. Effects of dietary macronutrients on serum urate: results from the OmniHeart trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;113(6):1593–9.

- Juraschek SP, Miller ER 3rd, Wu B, White K, Charleston J, Gelber AC, et al. A Randomized Pilot Study of DASH Patterned Groceries on Serum Urate in Individuals with Gout. Nutrients. 2021;13(2).

- Rai SK, Fung TT, Lu N, Keller SF, Curhan GC, Choi HK. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, Western diet, and risk of gout in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j1794.

- FitzGerald JD, Dalbeth N, Mikuls T, Brignardello-Petersen R, Guyatt G, Abeles AM, et al. 2020 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Management of Gout. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(6):744–60.

- Hidalgo-Mora JJ, García-Vigara A, Sánchez-Sánchez ML, García-Pérez M, Tarín J, Cano A. The Mediterranean diet: A historical perspective on food for health. Maturitas. 2020;132:65–9.

- Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, Covas MI, Corella D, Arós F, et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(25):e34.

- Mente A, de Koning L, Shannon HS, Anand SS. A systematic review of the evidence supporting a causal link between dietary factors and coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(7):659–69.

- Guasch-Ferré M, Bulló M, Babio N, Martínez-González MA, Estruch R, Covas MI, et al. Mediterranean diet and risk of hyperuricemia in elderly participants at high cardiovascular risk. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(10):1263–70.

- Yokose C, McCormick N, Rai SK, Lu N, Curhan G, Schwarzfuchs D, et al. Effects of Low-Fat, Mediterranean, or Low-Carbohydrate Weight Loss Diets on Serum Urate and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Secondary Analysis of the Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial (DIRECT). Diabetes Care. 2020;43(11):2812–20.

- Salas-Salvadó J, Bulló M, Babio N, Martínez-González M, Ibarrola-Jurado N, Basora J, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with the Mediterranean diet: results of the PREDIMED-Reus nutrition intervention randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(1):14–9

- Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2008. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(10):3136–41.

- Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Willett W, Curhan G. Purine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in men. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(11):1093–103.

- Schiavo L, Favrè G, Pilone V, Rossetti G, De Sena G, Iannelli A, et al. Low-Purine Diet Is More Effective Than Normal-Purine Diet in Reducing the Risk of Gouty Attacks After Sleeve Gastrectomy in Patients Suffering of Gout Before Surgery: a Retrospective Study. Obes Surg. 2018;28(5):1263–70.

- Obesity and overweight Factsheet. 2021.

- Glynn RJ, Campion EW, Silbert JE. Trends in serum uric acid levels 1961–1980. Arthritis Rheum. 1983;26(1):87–93.

- Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Curhan G. Obesity, weight change, hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of gout in men: the health professionals follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(7):742–8.

- Maglio C, Peltonen M, Neovius M, Jacobson P, Jacobsson L, Rudin A, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on gout incidence in the Swedish Obese Subjects study: a non-randomised, prospective, controlled intervention trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(4):688–93.

- Yeo C, Kaushal S, Lim B, Syn N, Oo AM, Rao J, et al. Impact of bariatric surgery on serum uric acid levels and the incidence of gout-A meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2019;20(12):1759–70.

- Nielsen SM, Bartels EM, Henriksen M, Wæhrens EE, Gudbergsen H, Bliddal H, et al. Weight loss for overweight and obese individuals with gout: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(11):1870–82.

- Lu J, Bai Z, Chen Y, Li Y, Tang M, Wang N, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on serum uric acid in people with obesity with or without hyperuricaemia and gout: a retrospective analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60(8):3628–34.

- Romero-Talamás H, Daigle CR, Aminian A, Corcelles R, Brethauer SA, Schauer PR. The effect of bariatric surgery on gout: a comparative study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(6):1161–5.

- Choi HK, Curhan G. Beer, liquor, and wine consumption and serum uric acid level: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(6):1023–9.

- Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Willett W, Curhan G. Alcohol intake and risk of incident gout in men: a prospective study. Lancet. 2004;363(9417):1277–81.

- Ralston SH, Capell HA, Sturrock RD. Alcohol and response to treatment of gout. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1988;296(6637):1641–2.

- Choi HK, Curhan G. Coffee, tea, and caffeine consumption and serum uric acid level: the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(5):816–21.

- Kiyohara C, Kono S, Honjo S, Todoroki I, Sakurai Y, Nishiwaki M, et al. Inverse association between coffee drinking and serum uric acid concentrations in middle-aged Japanese males. Br J Nutr. 1999;82(2):125–30.

- Choi HK, Willett W, Curhan G. Coffee consumption and risk of incident gout in men: a prospective study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(6):2049–55.

- Choi HK, Curhan G. Coffee consumption and risk of incident gout in women: the Nurses’ Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(4):922–7.

- Choi HK, Liu S, Curhan G. Intake of purine-rich foods, protein, and dairy products and relationship to serum levels of uric acid: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(1):283–9.

- Dalbeth N, Gracey E, Pool B, Callon K, McQueen FM, Cornish J, et al. Identification of dairy fractions with anti-inflammatory properties in models of acute gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(4):766–9.

- Dalbeth N, Wong S, Gamble GD, Horne A, Mason B, Pool B, et al. Acute effect of milk on serum urate concentrations: a randomised controlled crossover trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(9):1677–82.

- Dalbeth N, Ames R, Gamble GD, Horne A, Wong S, Kuhn-Sherlock B, et al. Effects of skim milk powder enriched with glycomacropeptide and G600 milk fat extract on frequency of gout flares: a proof-of-concept randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(6):929–34.

- Stirpe F, Della Corte E, Bonetti E, Abbondanza A, Abbati A, De Stefano F. Fructose-induced hyperuricaemia. Lancet. 1970;2(7686):1310–1.

- Choi JW, Ford ES, Gao X, Choi HK. Sugar-sweetened soft drinks, diet soft drinks, and serum uric acid level: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(1):109–16.

- Choi HK, Willett W, Curhan G. Fructose-rich beverages and risk of gout in women. JAMA. 2010;304(20):2270–8.

- Choi HK, Curhan G. Soft drinks, fructose consumption, and the risk of gout in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7639):309–12.