Central Line Associated Blood Stream Infection [CLABSI]

Dr. Abha Sharma*Dr. Anshuman Srivastava* Dr. Smita Nath*

*Assistant Professor (Medicine), UCMS, Delhi

https://meditropics.com/ra-2022-2/

Introduction

Most of the patients who are admitted in hospital require intravenous access which most commonly is done through peripheral intravenous catheter but if prolonged intravenous therapy or some major surgeries are planned then usage of central venous catheters have been increased. Anything that breaches the protective barrier of skin has tendency to introduces microorganisms in blood stream which can have manifestation ranging from none to fatal. Since the introduction of central venous catheterisation in 1929 by Forssmann who received Nobel Prize in in Medicine along with two of his colleagues in 1956, it has become essential component of modern medicine which is being used in haemodialysis, hemodynamic monitoring and to administer intravenous fluids, nutritional solution, medicines and blood transfusions [1]

In recent years, the focus has been shifted to the flipside of this life changing invention and some life threatening complications of central venous catheters were identified like catheter related blood stream infection, venous thrombosis, air embolism etc. In this chapter we will discuss about catheter related blood stream infection (CRBSI) or Central line associated blood stream infection (CLABSI).

Definition

There is no single definition of this entity. Catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI) is defined as the presence of bacteraemia originating from an intravenous catheter proven by quantitative culture of the catheter tip or by differences in growth between catheter and peripheral venepuncture blood culture specimens. When the cause is associated with central venous catheters then it is called Central line associated blood stream infection (CLABSI). Risk of developing CRBSI is 64 times greater due to central venous catheters than peripheral venous catheters. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has divided catheter related infections into various categories as following: [2,3,4]

- Catheter colonization– It is defined by significant growth of a microorganism [>15 colony-forming units (CFU) in semiquantitative culture or >100 CFU in quantitative culture] from the catheter surface in the absence of accompanying clinical symptoms or bacteraemia.

Local CRI- It has been subdivided into following subtypes:

- Exit site infection: It is diagnosed when the clinical signs of inflammation (e.g. redness, swelling, pain, purulent exudate) are located within 2 cm from the catheter insertion site, in the absence of concomitant blood stream infection.

- Tunnel infection: Tunnel infection is labelled when the clinical signs of infection are more than 2 cm from exit site along the subcutaneous part of the CVC, in the absence of concomitant blood stream infection.

- Pocket infection: Pocket infection is diagnosed when the sub-cutaneous pocket of an implanted port system shows clinical signs of infection and inflammation, in the absence of concomitant blood stream infection.

- Infusate-related BSI. When same organism grow from the infusate and blood cultures (preferably percutaneously drawn) with no other identifiable source of infection.

- Catheter-related bloodstream infections. While the CDC distinguishes CRBSI from catheter-associated BSI (CABSI)—the latter being considered if a patient had a CVC ≤48 h before the development of the BSI that is not related to an infection at another site.

However, some people have proposed a distinction between ‘definite’, ‘probable’ and ‘possible’ CRBSI for routine clinical use based on clinical findings and culture reports [5,6]

Epidemiology

CLABSI are important cause of morbidity and mortality specially in patients who are admitted in intensive care units. According to the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance system of the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, the median rate of CRBSI in intensive care units of all types ranges from 1.8 to 5.2 per 1000 catheter days with the rate of about 25.6% and in India it is reported to be around 27% which not only prolong the hospitalisation and healthcare cost but ultimately lead to increased risk of septicemia by 4-14% and death by 12-25%. [7,8,9]

Risk Factors

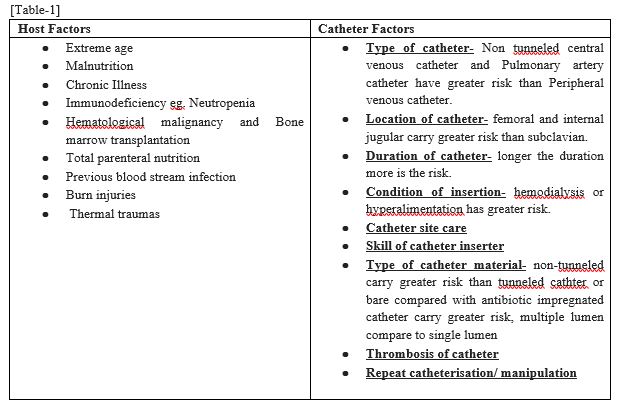

Blood stream infections can be classified according to host factors and catheter factors [10-12] [Table 1]

Pathogenesis

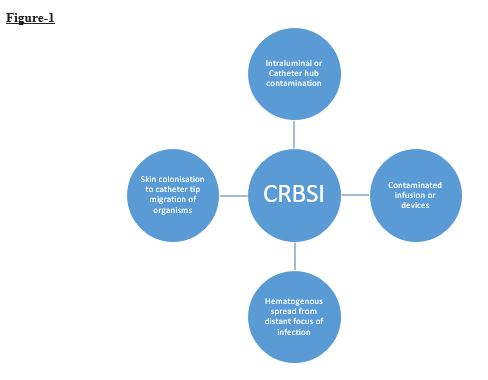

- After insertion of a catheter, a biofilm forms on the inner and outer surface of the catheter. Under non-sterile conditions, bacteria migrate from catheter hub along the catheter track from skin and/or down the lumen where bacteria get embedded in protein sheath. Within hours, the colonization of bacteria on outer and inner luminal surfaces. There is a lag time of 3-4 days during which the risk of CRBSI is low during which bacteria reach a threshold number to cause infection. Once CRBSI occurs, it triggers a systemic inflammatory response leading to fever, leukocytosis which may progress to septic shock and multiple organ failure. Some of the bacteria detach from the biofilm and spread and lead to the complications like septic thrombosis, endocarditis and septic arthritis increase when there is an adherent thrombus or if the bacteria become resistant to antibiotics. There are four sources of infections have been explaind which are shown in figure 1. [13-17]

Etiology

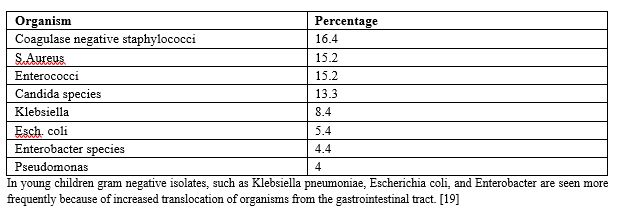

Common pathogens in decreasing order of frequency include [Table-2]

United states Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Healthcare Safety Network from 2011-2014 [18] [Table-2]

In young children gram negative isolates, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and Enterobacter are seen more frequently because of increased translocation of organisms from the gastrointestinal tract. [19]

Diagnosis

CRBSI is a diagnosis of exclusion and there is no microbiologic gold standard to establish the diagnosis.

Bacteremia or fungemia in a patient who has intravascular device and >1 positive blood culture result obtained from the peripheral vein, clinical manifestations of infections (fever, chills, and or hypotension) demonstrating that the infection is caused by the catheter and exclusion of other primary focus of infection are fundamental to establish the diagnosis of CRBSI. [20]

Clinical Manifestation

- Fever with chills

- Local signs of infection at catheter insertion site- redness, pus discharge.

- Signs of sepsis- hemodynamic instability, altered mental state, septic emboli.

When to suspect CRBSI?

In a patient with intravenous catheter CSBI should be suspected if patient develops:

- fever with chills or other signs of sepsis, even without local signs of infection, with no other source of infection

- metastatic infections due to hematogenous spread of microorganisms or septic emboli.

- Persistent or recurrent bacteremia caused by microorganisms that colonize the skin.

Sample collection for culture:

Catheter sample- There is no role of catheter culture at the time of catheter removal. The positive catheter culture is not diagnostic of CRBSI. Also, endoluminal brushing which used to be a part of sample collection is not done because of risk of pathogen dissemination. [21]

Blood culture- 2 sets of blood culture samples (atleast 20ml) are collected from 2 peripheral veins prior to antibiotic therapy, if not feasible then one sample can be drawn from peripheral vein and other from catheter. Blood cultures should not be solely from catheter because of risk of contamination from skin.

Others- Contaminated infusate should be sent for culture. [22-24]

Steps to be taken before removal of CVC [25]

- Rule out other possible sources of infection by clinical examination and imaging procedures (if necessary).

- Inspect the catheter insertion site or pocket or tunnel for signs of local infection. Palpate the pocket or tunnel.

- Take one pair of blood cultures (aerobic and anaerobic) from the catheter and one from a peripheral vein for microbiological evaluation and determine the differential time to positivity between the peripheral and catheter blood culture sample.

- In case of multi lumen CVC, separate blood cultures may be drawn from each lumen.

Diagnostic criteria for CRBSI:

In absence of any source of infections, following reports may attribute to diagnosis of catheter related blood stream infection-

- One or more blood culture bottles positive for S.aureus, enterococci, Enterobacteriaceae (eg, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella species, Enterobacter species), Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

- One or more blood culture bottles positive forCandida species (except in premature neonates)

Two or more blood culture bottles positive for coagulase-negative staphylococci or other common commensals (eg, Corynebacterium species [not Corynebacterium diphtheriae], Cutibacterium species, viridans group streptococci), Bacillus species [not Bacillus anthracis]. [3]

Complications of CRBSI

The patients may present with or can lead to life threatening complications due to CRBSI.

- Septic thrombophlebitis- It is defined as venous thrombosis associated with sepsis and complicated CRBSI is suspected when sepsis persists even after 72hours of appropriate treatment. [26]

- Infective endocarditis- It is defined as infection of single or multiple heart valves and suspected in patient of CRBSI or bacteremia for more than 48-72hours with pathogens who are typically associated with IE. [27]

- Metastatic musculoskeletal infections- It includes infections like septic arthritis, osteomyelitis which occurs in patient with bacteremia due to seeding of bone or joint and presents as acute onset pain and swelling of joint or worsening of musculoskeletal pain. [28]

Management

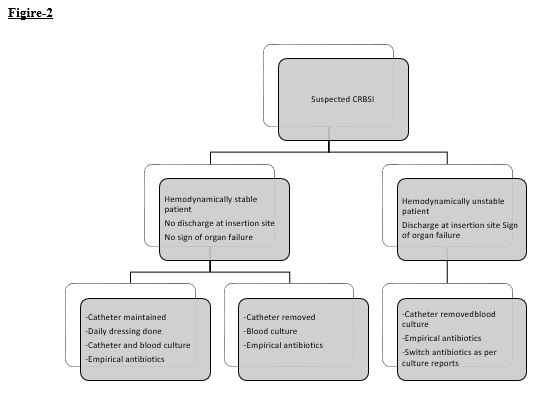

- Approach to suspected CRBSI is mentioned in figure- 2.

- The management begins with catheter removal and antibiotic treatment.

- If catheter removal is not feasible eg if there is no alternative access site or sites are limited, the patient has a bleeding diathesis, patient declines removal, or quality of life issues take priority over the need for catheter reinsertion at another site, a decision regarding catheter salvage or guidewire exchange must be made.

- Multidisciplinary approach with help of Infectious disease, cardiologist or surgeon consultation should be taken when suspicion of drug resistant gram negative bacterial or fungal infections, in situ endovascular implant or orthopedic hardware, metastatic infection or mycotic aneurysm or infection of vascular graft is present.

- If catheter has not been removed, repeat blood culture 72 hours after starting antibiotic therapy. If blood culture is positive, remove catheter.

- Empirical antibiotic therapy-It should be guided by gram stain results and depends on patient’s condition, risk factors and likely pathogen involved in that particular center.

- For gram positive organisms specially Staph aureus and MRSA – Vancomycin, Daptomycin, Linezolid.

- For gram-negative bacilli- ceftriaxone gives a good cover for gram negative infections but Ceftazidime, Cefepime, piperacillin-tazobactam, quinolones or aminoglycosides, imipenem and meropenem are preferred if there is neutropenia, severe burns, or hemodynamic instability, because they cover antipseudomonal beta-lactam group.

- Usually, duration of antibiotic therapy varies from 5-7 days and it can be extended upto 14 days in patients with endovascular implants and orthopedic hardware.

- Candida infection should be covered in the presence of total parenteral nutrition, femoral catheter, prolonged use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, hematologic malignancy, transplant recipient, candida infection at other sites. Echinocandin, or in selected patients, fluconazole is the first choice to treat candida.

- Patients are monitored for relapse and metastatic infections. Surveillance blood cultures are done to demonstrate the clearance of bacteremia after antibiotic treatment.

- Ideally, antibiotic therapy should be administered for at least two to three days following catheter removal, prior to catheter replacement [29]. At the time of catheter replacement, the patient should be hemodynamically stable with negative blood cultures for at least 48 to 72 hours (at least five days for detection of recurrent candidemia) and no sequelae of bloodstream infection [30].

Prevention of CRBSI

It starts from adherence to all the aseptic techniques starting from maintaining hand hygiene to insertion of catheter to dressing changes.

An appropriate Catheter should be inserted only if indication is there in the appropriate catheter insertion site and should be removed when no longer indicated. [31-33]

- Clean the site with an antiseptic 70% alcohol, tincture of iodine or > 0.5% chlorhexidine preparation with alcohol and allow to dry before CVC insertion.

- Use a chlorhexidine/silver sulfadiazine or minocycline/rifampin -impregnated CVC if catheter is expected to stay for > 5 days. CVC should have minimum number of lumens and insert it aseptically under ultrasound guidance to minimize the number of attempts.

- Use sterile gauze or sterile, transparent, semipermeable dressing to cover the catheter site. Use dressings impregnated with Chlorhexidine except in neonates to reduce the incidence of CRBSI. Change the dressing if it becomes loose/ damp or soiled. For short term CVC, change dressing every 2 days for gauze dressings and 7 days for transparent dressings.

- There is no need of anticoagulation or systemic antibiotic prophylaxis before insertion of CVC. Antibiotic lock solution should be used in patients with long term catheter with history of multiple CRBSI.

- Monitor the catheter site through the dressing regularly or visually while changing the dressing. Dressing should be removed if there is local site tenderness, fever with no other cause or clinical features of CRBSI.

- Patient should have skin-wash with 2% Chlorhexidine daily to prevent infection.

- Guidewire exchange should be done to only to replace a non-tunneled malfunctioning catheter and should not be used routinely to prevent infection or replace a suspected infected catheter.

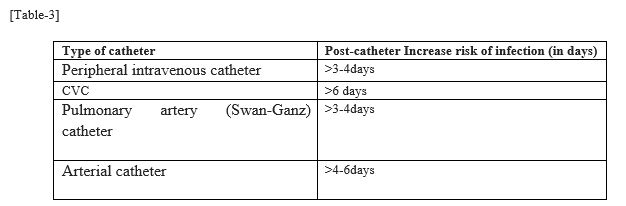

- One should remember the duration of post-catheterization which increases the risk of infection among different type of devices to tackle the issue before it arises.

Risk of infection increases after few days as mentioned in [Table-3]

Conclusion

Catheter related infection has a frequent occurrence and qualifies for both nosocomial as well as iatrogenic infection. If identified and treated on time then it amounts to unhappening form of infection but if there is a delay in diagnosis and management, it can lead to life threatening complications and death. If the guidelines of aseptic procedures, hand hygiene and daily dressing care are followed vigorously then it can reduce the burden of disease morbidity and mortality in hospitalised and critical patients tremendously.

References

- Sette P, Dorizzi RM, Azzini AM. Vascular access: an historical perspective from Sir William Harvey to the 1956 Nobel prize to André F. Cournand, Werner Forssmann, and Dickinson W. Richards. J Vasc Access. 2012 Apr-Jun;13(2):137-44. doi: 10.5301/jva.5000018. PMID: 21983826.

- Pearson ML, Hierholzer WJ, Garner JS et al. Guideline for prevention of intravascular device-related infections. Am J Infect Control 1996; 24: 262–293.

- O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns L etal. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52: e162–e193.

- O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Dellinger EP et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. MMWR Recomm Rep 2002; 51(RR-10): 1–36.

- Hentrich M, Schalk E, Schmidt-Hieber M, Chaberny I, Mousset S, Buchheidt D, Ruhnke M, Penack O, Salwender H, Wolf HH, Christopeit M, Neumann S, Maschmeyer G, Karthaus M; Infectious Diseases Working Party of the German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology. Central venous catheter-related infections in hematology and oncology: 2012 updated guidelines on diagnosis, management and prevention by the Infectious Diseases Working Party of the German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology. Ann Oncol. 2014 May;25(5):936-47. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt545. Epub 2014 Jan 7. PMID: 24399078.

- Boersma RS, Jie KS, Verbon A, van Pampus EC, Schouten HC. Thrombotic and infectious complications of central venous catheters in patients with hematological malignancies. Ann Oncol. 2008 Mar;19(3):433-42. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm350. Epub 2007 Oct 24. PMID: 17962211.

- Patil HV, Patil VC, Ramteerthkar MN, Kulkarni RD. Central venous catheter-related bloodstream infections in the intensive care unit. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2011 Oct;15(4):213-23. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.92074. PMID: 22346032; PMCID: PMC3271557.

- Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati G, Kainer MA, Lynfield R, Maloney M, McAllister-Hollod L, Nadle J, Ray SM, Thompson DL, Wilson LE, Fridkin SK; Emerging Infections Program Healthcare-Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Use Prevalence Survey Team. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med. 2014 Mar 27;370(13):1198-208. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306801. PMID: 24670166; PMCID: PMC4648343.

- Deliberato RO, Marra AR, Corrêa TD, Martino MD, Correa L, Dos Santos OF, Edmond MB. Catheter related bloodstream infection (CR-BSI) in ICU patients: making the decision to remove or not to remove the central venous catheter. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032687. Epub 2012 Mar 5. PMID: 22403696; PMCID: PMC3293859.

- Gahlot R, Nigam C, Kumar V, Yadav G, Anupurba S. Catheter-related bloodstream infections.Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2014;4(2):162-167. doi:10.4103/2229-5151.134184

- Tokars JI, Cookson ST, McArthur MA, Boyer CL, McGeer AJ, Jarvis WR. Prospective evaluation of risk factors for bloodstream infection in patients receiving home infusion therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1999 Sep 7;131(5):340-7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-5-199909070-00004. PMID: 10475886.

- Maki DG, Kluger DM, Crnich CJ. The risk of bloodstream infection in adults with different intravascular devices: a systematic review of 200 published prospective studies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006 Sep;81(9):1159-71. doi: 10.4065/81.9.1159. PMID: 16970212.

- Salzman MB, Isenberg HD, Shapiro JF, Lipsitz PJ, Rubin LG. A prospective study of the catheter hub as the portal of entry for microorganisms causing catheter-related sepsis in neonates. J Infect Dis. 1993 Feb;167(2):487-90. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.2.487. PMID: 8421188.

- Snydman DR, Gorbea HF, Pober BR, Majka JA, Murray SA, Perry LK. Predictive value of surveillance skin cultures in total-parenteral-nutrition-related infection. Lancet. 1982 Dec 18;2(8312):1385-8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)91281-8. PMID: 6129473.

- Maki DG. Nosocomial bacteremia. An epidemiologic overview. Am J Med. 1981 Mar;70(3):719-32. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90603-3. PMID: 7211906.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update: Delayed onset Pseudomonas fluorescens bloodstream infections after exposure to contaminated heparin flush–Michigan and South Dakota, 2005-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006 Sep 8;55(35):961-3. Erratum in: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006 Oct 13;55(40):1100. PMID: 16960550.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Pseudomonas bloodstream infections associated with a heparin/saline flush–Missouri, New York, Texas, and Michigan, 2004-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005 Mar 25;54(11):269-72. PMID: 15788991.

- Weiner LM, Webb AK, Limbago B, Dudeck MA, Patel J, Kallen AJ, Edwards JR, Sievert DM. Antimicrobial-Resistant Pathogens Associated With Healthcare-Associated Infections: Summary of Data Reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011-2014. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016 Nov;37(11):1288-1301. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.174. Epub 2016 Aug 30. PMID: 27573805; PMCID: PMC6857725.

- Page S, Abel G, Stringer MD, Puntis JW. Management of septicaemic infants during long-term parenteral nutrition. Int J Clin Pract. 2000 Apr;54(3):147-50. PMID: 10829356.

- Baron EJ, Miller JM, Weinstein MP, Richter SS, Gilligan PH, Thomson RB Jr, Bourbeau P, Carroll KC, Kehl SC, Dunne WM, Robinson-Dunn B, Schwartzman JD, Chapin KC, Snyder JW, Forbes BA, Patel R, Rosenblatt JE, Pritt BS. A guide to utilization of the microbiology laboratory for diagnosis of infectious diseases: 2013 recommendations by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM)(a). Clin Infect Dis. 2013 Aug;57(4):e22-e121. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit278. Epub 2013 Jul 10. PMID: 23845951; PMCID: PMC3719886.

- Miller JM, Binnicker MJ, Campbell S, Carroll KC, Chapin KC, Gilligan PH, Gonzalez MD, Jerris RC, Kehl SC, Patel R, Pritt BS, Richter SS, Robinson-Dunn B, Schwartzman JD, Snyder JW, Telford S 3rd, Theel ES, Thomson RB Jr, Weinstein MP, Yao JD. A Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases : 2018 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiology. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Aug 31;67(6):e1-e94. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy381. PMID: 29955859; PMCID: PMC7108105.

- Chatzinikolaou I, Hanna H, Hachem R, Alakech B, Tarrand J, Raad I. Differential quantitative blood cultures for the diagnosis of catheter-related bloodstream infections associated with short- and long-term catheters: a prospective study. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004 Nov;50(3):167-72. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2004.07.007. PMID: 15541601.

- Peterson LR, Smith BA. Nonutility of catheter tip cultures for the diagnosis of central line-associated bloodstream infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Feb 1;60(3):492-3. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu845. Epub 2014 Oct 29. PMID: 25355902.

- Lai YL, Adjemian J, Ricotta EE, Mathew L, O’Grady NP, Kadri SS. Dwindling Utilization of Central Venous Catheter Tip Cultures: An Analysis of Sampling Trends and Clinical Utility at 128 US Hospitals, 2009-2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 Oct 30;69(10):1797-1800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz218. PMID: 30882880; PMCID: PMC6821238.

- Hentrich M, Schalk E, Schmidt-Hieber M, Chaberny I, Mousset S, Buchheidt D, Ruhnke M, Penack O, Salwender H, Wolf HH, Christopeit M, Neumann S, Maschmeyer G, Karthaus M; Infectious Diseases Working Party of the German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology. Central venous catheter-related infections in hematology and oncology: 2012 updated guidelines on diagnosis, management and prevention by the Infectious Diseases Working Party of the German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology. Ann Oncol. 2014 May;25(5):936-47. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt545. Epub 2014 Jan 7. PMID: 24399078.

- Sinave CP, Hardy GJ, Fardy PW. The Lemierre syndrome: suppurative thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein secondary to oropharyngeal infection. Medicine (Baltimore). 1989 Mar;68(2):85-94. PMID: 2646510.

- Anderson DJ, Murdoch DR, Sexton DJ, Reller LB, Stout JE, Cabell CH, Corey GR. Risk factors for infective endocarditis in patients with enterococcal bacteremia: a case-control study. Infection. 2004 Apr;32(2):72-7. doi: 10.1007/s15010-004-2036-1. PMID: 15057570.

- Trampuz A, Piper KE, Jacobson MJ, Hanssen AD, Unni KK, Osmon DR, Mandrekar JN, Cockerill FR, Steckelberg JM, Greenleaf JF, Patel R. Sonication of removed hip and knee prostheses for diagnosis of infection. N Engl J Med. 2007 Aug 16;357(7):654-63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061588. PMID: 17699815.

- Lee YM, Ryu BH, Hong SI, Cho OH, Hong KW, Bae IG, Kwack WG, Kim YJ, Chung EK, Kim DY, Lee MS, Park KH. Clinical impact of early reinsertion of a central venous catheter after catheter removal in patients with catheter-related bloodstream infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021 Feb;42(2):162-168. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.405. Epub 2020 Sep 9. PMID: 32900398.

- Daneman N, Downing M, Zagorski BM. How long should peripherally inserted central catheterization be delayed in the context of recently documented bloodstream infection? J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012 Jan;23(1):123-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.09.024. PMID: 22221476.

- O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, Dellinger EP, Garland J, Heard SO, Lipsett PA, Masur H, Mermel LA, Pearson ML, Raad II, Randolph AG, Rupp ME, Saint S; Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) (Appendix 1). Summary of recommendations: Guidelines for the Prevention of Intravascular Catheter-related Infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 May;52(9):1087-99. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir138. PMID: 21467014; PMCID: PMC3106267.

- Gil RT, Kruse JA, Thill-Baharozian MC, Carlson RW. Triple- vs single-lumen central venous catheters. A prospective study in a critically ill population. Arch Intern Med. 1989 May;149(5):1139-43. PMID: 2497712.

- Raad I, Umphrey J, Khan A, Truett LJ, Bodey GP. The duration of placement as a predictor of peripheral and pulmonary arterial catheter infections. J Hosp Infect. 1993 Jan;23(1):17-26. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(93)90126-k. PMID: 8095944.