https://meditropics.com/1586-2/

*Arnav Khanna, **Sameer Gulati, ***Ghanshyam Pangtey

*Post Graduate Resident, **Professor, ** *Director Professor, Department of Medicine, LHMC

Abstract

A 26-year-old male from Delhi presented with high-grade fever (afebrile for 2 days), jaundice, abdominal pain, dry cough, and severe shortness of breath. His oxygen saturation was low at 70%, and examination revealed signs of respiratory distress, icterus, hepatosplenomegaly, and a notable eschar in the right iliac fossa. Laboratory tests indicated leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and deranged liver function tests and slightly elevated Ck-MB. Chest X-rays showed multiple inhomogeneous opacities and a “bat wing” pattern, while rapid tests for dengue, malaria, and typhoid were negative, but IgM for scrub typhus came out to be positive by ELISA. Despite initial treatment, the patient showed minimal improvement. A CECT scan revealed b/l ground-glass opacities, lymphadenopathy, and pleural effusions. The patient’s inflammatory markers were discordant, and an H-score suggested secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). Treatment was escalated to meropenem and high-dose corticosteroids. Over the next few days, the patient improved clinically and in laboratory parameters, leading to discharge after 13 days of hospitalization.

Introduction

Scrub typhus, caused by the Orientia tsutsugamushi bacterium, transmitted by bite of mite larvae(chiggers), poses significant health risks in endemic regions, often presenting with a spectrum of clinical manifestations. Among these, myocarditis and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) can emerge as severe complications, leading to significant morbidity. Myocarditis may result in cardiac dysfunction and arrhythmias, while ARDS contributes to critical respiratory failure. Additionally, the infection can trigger secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), a severe hyper-inflammatory response characterized by excessive immune activation. This triad of complications underscores the complexity of scrub typhus and the necessity for vigilant clinical evaluation. Here we present a case of an immunocompetent individual presenting with scrub typhus complicated by ARDS, myocarditis, hepatitis and secondary HLH.

Case Presentation

A 26-year-old male, resident of Delhi, presented with complaints of high-grade fever(103oF) for 5 days. There was yellowish discoloration of eyes, abdominal pain, dry cough and acute onset dyspnea (MMRC grade 4) past 3 days. He was afebrile for 2 days prior to admission. There was no history of insect bite.

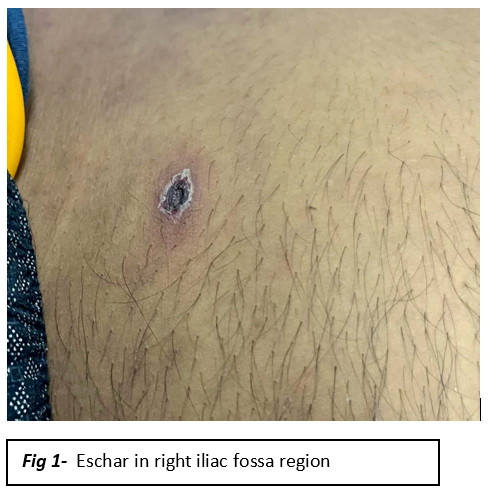

On examination, oxygen saturation 70% (room air), respiratory rate -34/minute. Icterus & bilateral pitting pedal edema was present. Eschar (2×1 cm) with erythematous edge noted in right iliac fossa (Figure1).

Systemic examination of abdomen showed tender hepatomegaly (18 cm) & splenomegaly (4 cm below left costal margin) seen. Respiratory examination decreased air entry and coarse crepitations in bilateral infra-axillary and infra-scapular areas.

Laboratory investigations prior to admission showed leukopenia and thrombocytopenia albeit on an improving trend. In hospital investigation showed platelet count-71000/ul, total bilirubin-6.1 mg/dl, direct bilirubin-3.7 mg/dl, SGOT-276 IU, SGOT-114 IU, Ck-NAC-137.8 U/l(26-171), Ck-MB-36.5 U/l(0-25), NT-pro BNP-710 pg/ml(<450),Trop-I-0.05 ng/ml & PCT- 2.6 ng/ml. ABG -type 1 respiratory failure Pao2/fiO2-195. Rapid kit tests for dengue, malaria and typhoid were negative. IgM dengue by ELISA was also negative. IgM scrub typhus (ELISA) was positive.

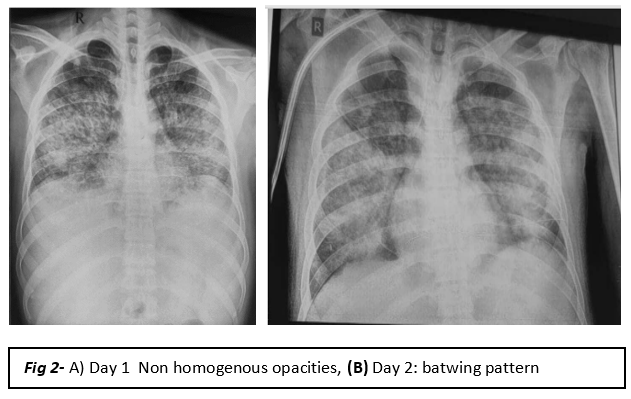

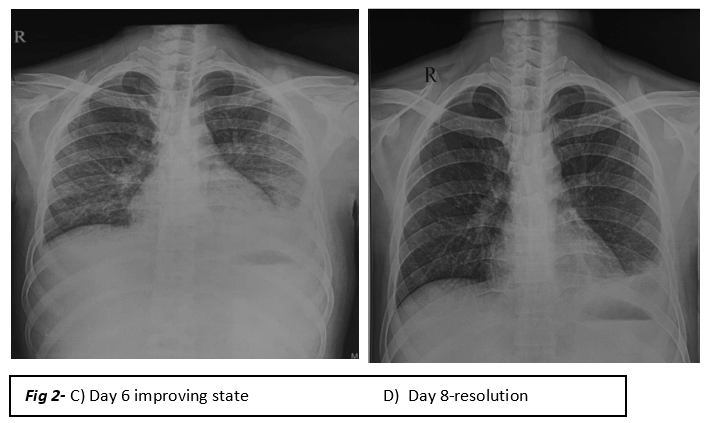

Chest x-ray showed multiple inhomogeneous confluent opacities with air bronchograms in bilateral lung fields. Chest x-ray on day 2 showed typical bat wing pattern opacity in bilateral lung fields( Figure2).

Despite treatment with diuretics, non-invasive ventilation, 3rd generation cephalosporin and doxycycline, patient showed minimal improvement.

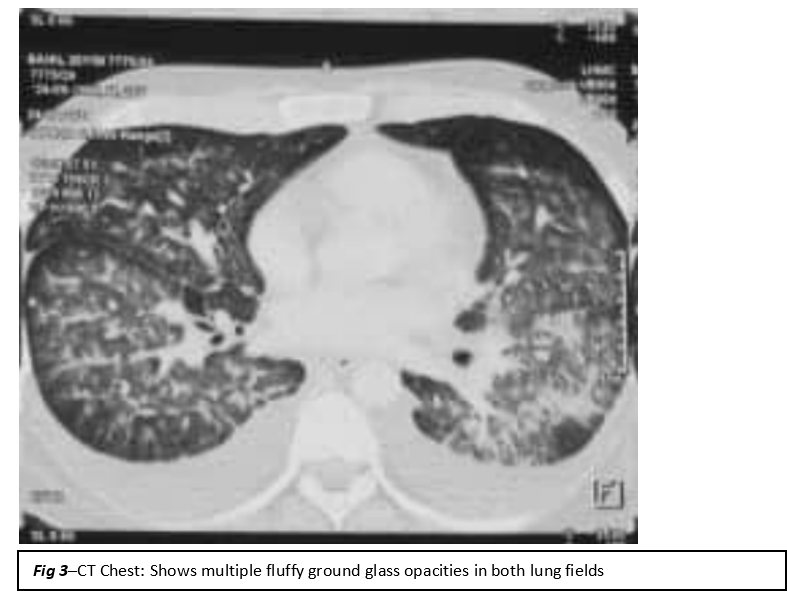

CECT chest & abdomen showed multiple fluffy ground glass opacities with some nodular consolidations with multiple lymph nodes in the mediastinum. Presence of bilateral pleural effusion, minimal pericardial effusion, hepatosplenomegaly and mild ascites noted. This was suggestive of infective etiology ( Figure 3).

There was a discordance between ESR (2 mm/hr) & CRP (132.23 mg/dl) with low plasma fibrinogen (208 mg/dl), high serum ferritin (5398 ng/ml). H-score for the patient was 166 (cutoff = 151 without inclusion of bone marrow). He was diagnosed having secondary HLH.

Antibiotics escalated to meropenem. Pulse steroid (Inj. Methylprednisolone) given for 3 days. Over the course of the next few days dramatic improvement in clinical and laboratory parameters noted. Resolution of radiographic findings on chest x-ray seen. Patient was discharged after 13 days of hospital stay.

Discussion

Scrub typhus is a serious infectious illness caused by the rickettsial bacterium Orientia tsutsugamushi. It poses a major public health threat in the Asia-Pacific region, particularly in the area referred to as the “tsutsugamushi triangle.” Covering 8 million square kilometers and impacting over 1 billion individuals in nations like India, Pakistan, Australia, and Japan, this triangular region presents a major public health danger with a high chance of death.1

A recent study on the impact of scrub typhus in India, found in the “tsutsugamushi triangle,” showed that around 25.3% of people with undifferentiated febrile illness have scrub typhus.2

Humans acquire the infection through larval trombiculid mite bites. The typical symptoms typically appear within 6 to 21 days after the incubation period and include fever, headache, muscle ache, and digestive issues. An “eschar” is a unique feature of scrub typhus, usually starting as a primary papular lesion at the location of the bite but may not be always present. Treatment should be started based on clinical suspicion and then confirmed with serological tests.

The pathophysiology of O tsutsugamushi involves vasculitis due to the infection of endothelial cells, leading to perivascular infiltration of T cells and monocytes or macrophages. Subsequently, a wide range of inflammatory responses occurs, with endothelial and non-endothelial cells producing various cytokines. This immune response can lead to severe complications such as hepatitis, renal failure, meningoencephalitis, and respiratory failure, including acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and occasionally myocarditis. Respiratory system involvement during scrub typhus ranges from 20–70% out of which ARDS is seen in 14% patients as was the case in our patient.3,4 The possible diagnosis of secondary HLH should also been considered alongside scrub typhus especially when patient is deteriorating despite appropriate treatment. Serum ferritin is a particularly sensitive indicator that reflects the disease activity, and can be used as an indicator for curative effect and the prognosis of HLH.5 Discordance between ESR and CRP values is also a subtle indicator that the patient has developed HLH as was seen in our patient also.

According to a systematic review of burden of scrub typhus in India, the overall case fatality rate from 75 studies was found to be 6.3% and from the 40 acute undifferentiated febrile illness studies was 7.6%. Regionally, the highest CFR was 8.5%, reported in North India, followed by 4.7%, reported in South India. However, the proportion of scrub typhus cases was higher in South India (55.5%) than in North India (31.5%). High case fatality rates were reported in patients with myocarditis (42.4%) followed by shock (39.6%), meningitis (35.5%), acute kidney injury (34.6%), ARDS (26.8%), hepatitis (23.2%), and thrombocytopenia (21.9%). Information on death among MODS cases was noted in 28 studies and was found to be 38.9%.6

Most of the laboratory-confirmed cases of scrub typhus in India occur in young adults exposed to scrub vegetation with a median age of 28.1 years. IgM ELISA, an accurate and accessible means of diagnosis, was used as the confirmatory test in a large proportion of studies (122 studies) and detected 87% of all cases.6 In a recent study evaluating the performance of molecular and serologic tests for the diagnosis of scrub typhus, ELISA was found to have a sensitivity of 94.2% and a specificity of 93.6%, which makes it a reliable test.7 Weil-Felix reaction is another test which can be employed but has poor sensitivity.

Conclusion

To conclude, we present a case of scrub typhus complicated by myocarditis, hepatitis, ARDS and secondary HLH. This case underscores the importance of early diagnosis and intervention in scrub typhus, particularly in endemic regions.

Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for scrub typhus in patients presenting with an acute undifferentiated febrile illness especially in endemic areas. The potential for severe complications necessitates a multidisciplinary approach to management. Future research should focus on understanding the mechanisms behind these complications, the impact of timely treatment, and strategies for improving patient education and awareness in endemic regions.

References

- Bonell A, Lubell Y, Newton PN, Crump JA, Paris DH. Estimating the burden of scrub typhus: A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(9): e0005838.

- Devasagayam E, Dayanand D, Kundu D, Kamath MS, Kirubakaran R, Varghese GM. The burden of scrub typhus in India: A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(7):e0009619.

- Abhilash K, Mannam PR, Rajendran K, John RA, Ramasami P. Chest radiographic manifestations of scrub typhus. J Postgrad Med. 2016;62(4):235-238.

- Wang CC, Liu SF, Liu JW, Chung YH, Su MC, Lin MC. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in scrub typhus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76(6):1148-1152.

- Imashuku S. Clinical features and treatment strategies of Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;44(3):259-272.

- Devasagayam E, Dayanand D, Kundu D, Kamath MS, Kirubakaran R, Varghese GM. The burden of scrub typhus in India: A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021 Jul 27;15(7): e0009619.

- Kannan K, John R, Kundu D, et al. Performance of molecular and serologic tests for the diagnosis of scrub typhus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(11): e0008747.